This sermon was originally preached at Messiah Evangelical Lutheran Church in East Setauket, New York.

Grace, mercy, and peace to you from God our Father and our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ.

Brothers and sisters: Last Sunday, we saw Peter being a model Christian. Jesus asked him and the other disciples to say who they thought he was, and Peter answered him correctly. “You are the Christ, the Son of the Living God.” Peter correctly identified Jesus as the Messiah, and he modeled a confession that we Christians repeat to this day. Today’s Gospel reading skips forward in time a little, where we see Peter being a model of a Christian again, but this time, he’s not going to be the kind of model we want to emulate.

The Bible is full of these sorts of models. One moment, we see an individual performing a great act of devotion and faith; the next, we see them blaspheming or acting out of unbelief. My favorite example of this is from Exodus, Chapter 24, when Moses, Aaron, Nadab, Abihu, and seventy of the elders of Israel go up onto Mount Sinai to have an audience with God after the people swear that they will do “all that the Lord has said” (Ex 24:8-13). Moses, Aaron, and the seventy-plus others actually see God, and share a feast with him; then Moses stays on the mountain and the rest go back to the camp. Skip ahead eight chapters, and what do you see? Aaron and the elders, who literally saw God sitting on a sapphire dais and then ate with him, proceed to build a golden idol in the shape of a calf and begin to offer it worship as if it was the God they just met. God’s people are often very bad at being who they’re called to be, and in our Gospel reading this morning, we see Peter following in the footsteps of his forefathers.

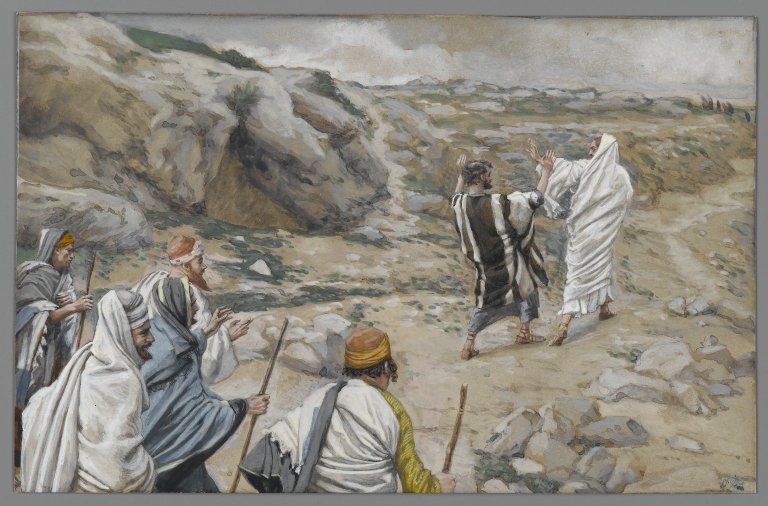

And what is it that Peter does? Matthew tells us. Jesus teaches the disciples about what needs to happen to him so that he can fulfill his mission as the Messiah. He tells them that he needs to go to Jerusalem, suffer at the hands of the authorities, be killed by them, and then be raised to life again by God on the third day following his death. Peter is listening to all this. But when he hears that Jesus is going to die, his mind closes on that detail like a steel trap. He doesn’t like it. He doesn’t want to hear it. The suffering and death is too much for him to comprehend. Surely this can’t be the plan? If this is God’s plan, he doesn’t want it to be this way. Surely this can’t happen? Jesus is his friend, his Rabbi. He can’t just let him die!

So Peter tells Jesus that whatever he’s thinking is crazy talk. “Jesus, this surely will not be your fate!” Peter doesn’t get it. He doesn’t get the fact that Jesus has to die. And he doesn’t hear that final part of what Jesus says, that Jesus will live. Jesus puts him in his place. “Get behind me Satan! You are my scandal” – “you are my stumbling block in carrying out the divine plan” – “because you are not thinking on the things of God but on the things of men!” And then Jesus follows with this: “If anyone wishes to come after me, let him deny himself and let him take up his cross and let him follow after me. For whoever desires to save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life on account of me will find it.”

“Let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow me.” I think, oftentimes, you and I probably think like Peter at the beginning of this exchange. We don’t want bad things to happen. We can’t fathom the idea of a loved one dying, nor can we imagine our own demise. We don’t like the idea of suffering. And really, why should we? Suffering is an inherently, patently bad thing, right? Dying is bad. It’s the result of the Fall, and therefore, the result of sin. And sin is the very essence of bad. So, we seek to avoid death and suffering in all their forms. We use all kinds of beauty treatments and surgeries to make ourselves look younger than we actually are. We hide the elderly away from the rest of society in nursing homes or “50+” communities because we tell them that it’s good for them. But it can often be because we really don’t want to see what’s coming–that we, too, shall age and lose our faculties. Society tells us that we have to live our best lives now, and live them forever, so we distract ourselves with drugs, alcohol, sex, technology, and money to keep us from thinking about the inevitable, or to fool ourselves into thinking that we’re staving off the inevitable. Or, we trust in ourselves to make it right, to fix the situation so that whatever bad thing we see coming our way will pass us by, that through our own efforts we will be able to live comfortably and, ideally, forever. We don’t want difficulty, pain and death for ourselves, and we certainly don’t want it for the people we like.

And then there’s the decay of our institutions. We don’t like seeing that, either. Looking at the state of the Church right now in America, things don’t look good. Congregations are closing because of financial insolvency. Membership is dropping. The majority of people aren’t raising their children in the faith anymore, and those children who were raised in the Church don’t seem to be sticking around. Our congregations are aging, and fewer and fewer seem to be coming in to replace those who die. Christian faith is often disparaged. America is no longer the bastion of Christendom it once seemed to be; the Church is the butt of jokes and the target of a lot of hate. And now with COVID, the fragility of many of our congregations has become greatly apparent, and we fear that many will close because they aren’t financially stable. And we hate to see this. We don’t want to see the churches we love disappear. So, out of fear of the worst, we try to bring it back through our efforts, adopting strategies to grow the church borrowed from worldly models that speak more to what people want to hear than what they need to hear, that reduce the Gospel message to platitudes instead of cold, hard, and yet liberating, truth. Or we become turned in on ourselves, ignoring the harsh reality of the situation while going on as if everything is normal.

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/49493993/this-is-fine.0.jpg)

And what is the one common denominator among all these examples that ties them to what happens with Peter? It is an unwillingness to take up one’s cross and follow Jesus. It is the desire to set one’s mind on earthly considerations rather than heavenly ones, to let earthly cares dominate, to trust in one’s own strength to overcome the world’s adversities rather than trusting in God and his mercy. Suffering is a cross. It’s a huge cross. And suffering is undeniably a bad thing. But by bearing it, we become more like Christ and grow in faith in him. Why? Because Jesus is found in suffering.

If you hang around a Lutheran Seminary long enough, you’ll undoubtedly hear the phrases “theology of glory” and “theology of the cross.” These come from Luther’s Heidelberg Disputation of 1518. Luther defines a theology of glory as one that tries to explain away or make excuses for what God is doing. If you know your book of Job, this is what Job’s friends do. They try to explain away the suffering Job has received from God in various ways–God’s mad at Job because Job did something bad, or Job must not have earned God’s favor, or God just has a mysterious reason, but Job deserves whatever he’s getting. It tries to get God off the hook for sending calamities against Job.

A theology of the cross, on the other hand, as Luther says, calls a thing what it is. A theology of the cross sees suffering and names it as such. The suffering Job receives is bad. And it’s from God. So God has given Job something bad, and we don’t know why. All we can do, and it’s what Job does, is trust that God is using it in a way that glorifies his name and that God will save Job because Job trusts in God’s promises.

Job trusts that his redeemer lives and will intercede for him on God’s behalf–that God will intercede for him with himself. And in our Gospel lesson this morning, we hear Jesus telling his disciples just how this will be. The Son of Man will suffer many things and die and be raised on the third day. Jesus will do his saving work through suffering. But how can someone deny himself, or herself, and follow Jesus, struggling along under the weight of a cross like his? It seems surely impossible. Jesus even died in the midst of his struggle.

But this is the theology of the cross at work. Jesus suffered and died, for us. And when he did, he overcame the power of sin, death, and hell. Peter didn’t want Jesus to do that because he didn’t understand what Jesus was going to do. Peter didn’t understand that it was all part of God’s divine plan, and he didn’t like what God’s plan looked like. Peter would have preferred to have been in God’s place to keep the bad parts of the plan from happening. But when Jesus suffered and died on the cross, he took all the suffering, death, loss, fear, and terror that we feel in this sin-wracked world and experienced them with us and for us. His suffering was the ultimate suffering. His strength is made perfect in weakness; he wins by “losing.” And his resurrection not only showed us that death is not the end; it also showed us that the sin and misplaced desires that keep us from trusting God’s plan and from clinging to him more closely isn’t the barrier we often think it is or want it to be. Because he suffered death and lives for our sake, by trusting in him, we can bear the crosses we experience in our lives, too, because he bore his cross for us. Moreover, he helps us bear our crosses. And if we stumble, he is there to pick us up, and when it seems like the cross of this life is too difficult to bear, that it would just be easier to give into despair or hedonism or anything else that distracts us from those “things of heaven,” we can look to Jesus. We see in his wounds that he knows what we are feeling all too well, and that those hands that were pierced through on our account bore as much as we do, and more. And those arms, once upon the cross extended, are now held open for us, inviting us to come to him and to leave behind those earthly distractions and fears; to find our life. When we see Jesus through the lens of the cross, we see what he has done, and we trust in him, even if we suffer. He had to suffer for us, and now our suffering brings us closer to him.

Who are we left with? Jesus.

This is what God wants for us, for us to find our life in his Son. My old seminary president, Dr. Dale Meyer, mentioned in a video conference I was in with him on Wednesday that he is more and more convinced that God, in his fatherly and loving way, strips more and more away from us–job, health, loved ones, and ultimately our life. The loss of these things are crosses that we must bear in this life, and we don’t know why God takes them from us, only that he does so in his wisdom. But as terrible as the bearing is, brothers and sisters, when these things are stripped away, what are we left with? We are left with Jesus. We will lose everything in this world, but Jesus. But in the end, he is all we need. Our life is in him. No matter the storms that come or the things we lose, the hardships that we carry that seem too difficult to bear, we will have life in him because of what he did for us, on that cross on Calvary’s hill so long ago. The Apostle Paul says it for us well in Romans 6:

“5 For if we have been united with him in a death like his, we shall certainly be united with him in a resurrection like his. 6 We know that our old self was crucified with him in order that the body of sin might be brought to nothing, so that we would no longer be enslaved to sin. 7 For one who has died has been set free from sin. 8 Now if we have died with Christ, we believe that we will also live with him. 9 We know that Christ, being raised from the dead, will never die again; death no longer has dominion over him. 10 For the death he died he died to sin, once for all, but the life he lives he lives to God. 11 So you also must consider yourselves dead to sin and alive to God in Christ Jesus.”

Peter didn’t understand that God’s plan was to save everyone through Jesus’ death and resurrection, at least not at this point of Matthew’s Gospel. He would, of course, later, at Easter and Pentecost. And Peter didn’t understand that he, too, would have to suffer in this life in order to find his life in Christ, but he eventually did. Jesus told Peter that he would on the banks of the Sea of Galilee after the resurrection: “Truly, truly, I say to you, when you were young, you used to dress yourself and walk wherever you wanted, but when you are old, you will stretch out your hands, and another will dress you and carry you where you do not want to go” (John 21:18). He was referring to Peter’s death, and in that, Peter modeled what he initially didn’t understand about bearing his cross. In fact, in addition to the cross of persecution that Peter experienced in his ministry, Peter bore a very real one, and he, too, was crucified by the Romans for the sake of the Gospel, for the sake of the Christ. We Christians living today, long after Jesus’ resurrection, dead to sin and alive in him, can bear our crosses and follow him in the assurance that in dying once for all, Christ paved the way and walks alongside us. Knowing this, we can say like Paul in Romans 5: “3 …we rejoice in our sufferings, knowing that suffering produces endurance, 4 and endurance produces character, and character produces hope, 5 and hope does not put us to shame, because God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit who has been given to us.”

The chances and changes of this life may bring us all kinds of sorrow and calamity, and the institutions we love may change in ways we could never imagine. But when we look to the cross of Christ and trust in him, knowing that the Father is working all things for our good and for his glory, we find our lives, resting safe in the arms of Jesus Christ. Amen.