Originally preached at Messiah Evangelical Lutheran Church, East Setauket, New York.

Grace, mercy, and peace to you from God our Father, and our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ. Amen.

When Martin Luther died, his friends found a slip of paper in his pocket with his final epitaph written upon it, a summation of his life’s work and teaching:

“No one can understand Virgil in his Bucolics and Georgics [poems about rural life] unless he has spent five years as a shepherd or farmer. No one understands Cicero in his letters unless he has served under an outstanding government for twenty years. No one should believe that he has tasted the Holy Scriptures sufficiently unless he has spent one hundred years leading churches with the prophets. That is why: 1. John the Baptist, 2. Christ, 3. The Apostles were a prodigious miracle. Do not profane this divine Aeneid, but bow down to it and honor its vestiges. We are all beggars. This is true.”

Luther, a man who had lived a life in the word of God and who spent decades studying and expounding upon it, writes this advice for those who would come after him: unless you’ve literally been working alongside the Apostles in the trenches of the church your whole life (and longer!), you’ll never be able to say, “I know enough about God and what the Scriptures say, I think I’m good, time for something else.” Indeed, even that’s not enough, because there are mysteries of the faith that a lifetime of study cannot elucidate. So bow down before the miracle of what God has done, because, as Luther wrote, wir sind alle Bettler, hoc est verum. We are all beggars, this is true. We deserve none of it, but God be praised, he has given us faith and life in abundance, indeed, a priceless gift that is worth more than anything we can possibly imagine, and we deserve none of it based on our merits alone.

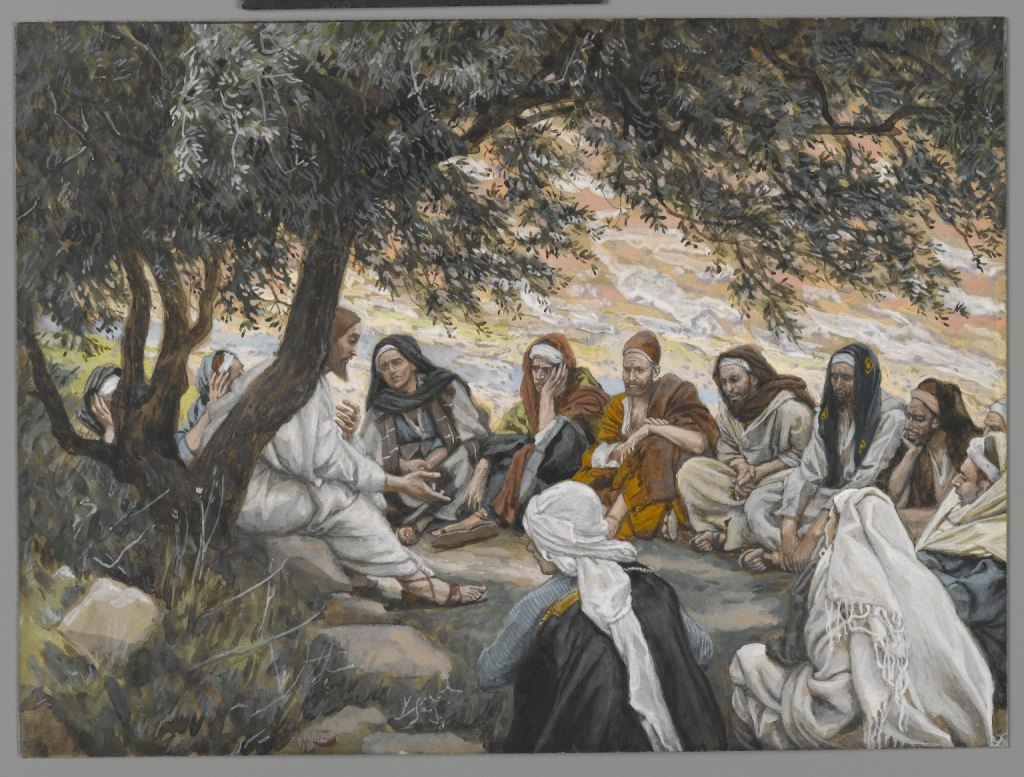

That is what our Gospel reading from Matthew is about this morning–the boundless grace of God for us. When Jesus is talking to the disciples, he illustrates just how limitless and free this grace of God is with the parable of the laborers in the vineyard. As we heard in the parable, the kingdom of heaven is like a man who owns a vineyard who goes out to hire laborers to work in the vineyard, agreeing to pay them a daily wage of a denarius (which in today’s dollars based on the current Troy ounce value of silver is worth about $2, but it was a day’s wage in the ancient world). The landowner goes out every couple of hours to hire more day laborers, telling them he’ll pay them a fair wage. Finally, at the eleventh hour, just before quitting time, he hires a fourth set of laborers who only work in the vineyard for an hour before being sent home. The landowner pays them all equally, a denarius for each of the latecomers, and a denarius for those who had been there since that morning.

The laborers who had been there since morning, though, were outraged. “Why do these Johnny-come-latelies get paid the same pay as us? Whatever happened to equal pay for equal work? They didn’t earn this!” The landowner replies, “I told you I’d pay you a denarius and I paid you a denarius. It’s my money, I can spend it how I please, so don’t worry about what I paid them.”

Now, if we were in their situation, wouldn’t we feel the same way about this, that perhaps we ought to have had a bigger share of pay for our work, or that those who came late should have been paid less? That only makes sense, does it not? Those who worked longer should be paid more than those who worked less? But, as a dearly departed pastor of mine once said, God is more generous than fair. If the kingdom of heaven is like this vineyard owner, then the kingdom of heaven operates according to God’s ideas of fairness, not our own. And that’s because God gives grace–not according to our works–but according to his righteousness.

It’s easy to want to put stock in one’s own works to earn God’s grace. That’s how we get ahead in this earthly life, after all. Most everything we do is based on earned merit. We work hard in school so that we can get into good universities or trade schools. We then work hard in order to graduate with honors and to get into the best graduate programs we can or to get the best jobs we can. And then we strive to make as much money as possible in order to achieve comfortable lives and to hear from our friends and families, “Job well done, you’ve done well for yourself!”

But where our righteousness is concerned, that’s a different matter. We can’t work our way toward being better people. Oh, folks have claimed that this was possible throughout history, probably most famously the fourth-century British monk, Pelagius, who claimed that God had given us the freedom of will to do that which is good and to choose not to sin; Pelagius thought that we could work our way to righteousness.

The problem with Pelagius’ understanding, however, is that he thought too highly of the ability of humans to do that which is right, and he was condemned as a heretic for claiming that people could actually earn God’s forgiveness by how they lived. (His teachings are likewise condemned.) When our first parents sinned, they made sin a part of the human condition, and so sin pervades all that humans do. We can’t have a sinless thought or desire if we are thinking with respect to our own ability. Even our desire to good for others is stained with some kind of selfishness. And certainly, if we want to stop sinning, we can’t will ourselves to do it. Remember what the Apostle Paul says in Romans 7? “For I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want is what I keep on doing. Now if I do what I do not want, it is no longer I who do it, but sin that dwells within me” (Romans 7:19-20). When we trust in our own wills to do that which is good, we make idols out of ourselves and our abilities–another sin!–and we are back to square one. We stand condemned.

We live in a Pelagian world that places pride in pulling oneself up by one’s bootstraps. Funnily enough, that phrase, “to pull oneself up by one’s bootstraps,” originally referred to an impossible task. You should try doing it sometime—you’ll end up looking silly, and you can’t do it. Yet somehow we made it the ultimate expression of self-reliance and the ultimate expression of the power of the will. But we cannot pull our righteousness up by the bootstraps. We cannot earn for ourselves that which God alone can give us, because when we try to do so, we deserve it less. We sin, and the wages of sin is death.

So let us return to the vineyard. By now you’ve probably figured out that the promised denarius is not a denarius, but God’s grace, the promise of eternal life. And when we answered the call of faith in Jesus to come into his vineyard, to trust in his saving work and to live and work in his kingdom, this is the “wage” we are promised and the one we will receive. And what could be a greater wage? But it’s not a wage based on any of our works. Our self-righteous works, when motivated by the self and not the Spirit, as the prophet Isaiah says, are like filthy rags in the sight of God; they don’t earn us anything from him because they are not from him. Instead, grace and eternal life is God’s gift to us who have heard his call and responded in faith, who have heard the Gospel and the promise that Jesus Christ died and rose **for you** that your sins should be forgiven and that you be made a child of God. This wage of eternal life is beyond price, worth more than any denomination of coinage, and certainly more than any of us deserve based on our works. But as I said before, God is more generous than fair, and he’s certainly more merciful than we can imagine. His mercy and his grace are boundless, and so all who have entered his vineyard, whether at the first hour or at the eleventh hour, receive the same, incredibly priceless gift of life in him.

But what of the jealousy of those already in the vineyard? I think Jesus is reminding the disciples and us that God makes no distinction between those who have been children of the kingdom for a long time and those who come later. Why should anyone be jealous when God adds to the number of those being saved? The church should not be marked by a mentality of “us vs. them” with regard to old and new believers–nor should we ever as a congregation. After all, a Christian should know that he or she is no better than anyone else, because we are all redeemed sinners. And at his Second Coming, when Jesus returns, there will be no jealousy or thinking that one is more deserving of God’s grace than another. Indeed, we should all be glad when new workers come into God’s vineyard, whatever the hour, because, having repented of their sin, they now share in the promise of the greatest gift of all, no matter who they were in their former life.

And what of the first being last and the last being first? Notice, when Jesus says that the first shall be last and the last shall be first, he’s not saying that those who come later are any better than those who come into the kingdom earlier. Those who came later aren’t given more, nor are those who came earlier deprived of any honor. They are all equal recipients of the grace of God in Christ–they all have received eternal life. There’s no great social upheaval, no making things topsy-turvy. All will receive that great, priceless gift. The order doesn’t really matter, if maybe only to prove a point. And so it is with us.

But perhaps this is a way that Jesus is teaching his disciples and us to remember that we are all beggars. Not one of us can say that we’ve been in the trenches with the saints forever; none of us can say that we’ve studied scripture enough not to need it and the promises it speaks to us. We’re all eleventh-hour people, purchased by the blood of the lamb to enter the kingdom. We have all been given the immeasurably boundless grace of God in Christ, and for that we should rejoice and be glad, because he grants it to us, who could certainly never earn it. We are all beggars, this is true, but thanks be to God, we have a God who is more generous than fair, who fills our beggar’s cup with the food of immortality, and who gives us far more than we could ever imagine. Amen.