Originally preached at Messiah Evangelical Lutheran Church, East Setauket, New York.

Perhaps it happened in the courtyard of the house while she was doing her chores, sweeping up leaves and dust to clean the cobblestones. Perhaps she was in the kitchen, preparing bread for the evening meal. Perhaps she was sitting in prayer in her chamber when it occurred. We do not know what Mary was doing that fateful day when the Lord’s messenger Gabriel found her to deliver her the news, but how wonderful and terrible his greeting to her must have seemed. Angels, of course, are generally frightening in their aspect and terrible to behold, and of course, their inhuman appearance strikes fear and dread into the hearts of those who see them. So to be going about one’s work when a creature from the heavenly realms appears in your home is startling, to say the least, if not frightening, even if that creature greets you with the words, “Rejoice, favored woman, the Lord is with you!”

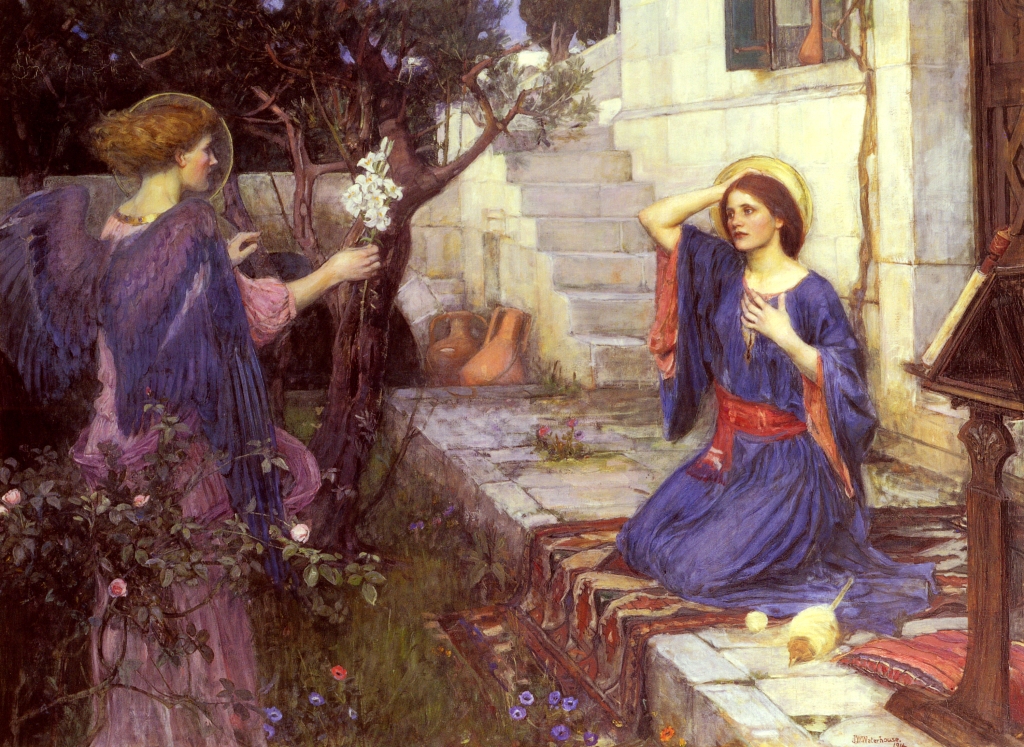

What must Gabriel have looked like to the young Mary? The old Basque carol “The Angel Gabriel from Heaven Came” describes him as having “wings of drifted snow and eyes of flame.” Perhaps he did appear this way. Artists have depicted the meeting in many different ways. Van Eyck painted him as a crowned man with wings of many colors. William Waterhouse depicted him as a young man with small wings bearing a lily to the Virgin as she sat in her garden. Henry Ossawa Tanner painted him as a bright mass of light, illuminating the chamber in which Mary sat. And George Hitchock never even painted him at all–Mary is merely in a field of lilies, seemingly by herself. But regardless of how Gabriel came to Mary or in what form, despite his words of greeting, Mary was taken aback and frightened. Luke, our Gospel writer, says that she was “deeply troubled” at his words.

And what must she have thought? Angels didn’t always have good news–very often, in the days of the Old Testament, they came to mete out God’s justice, or foretell a future event of great significance. And they often strove on the battlefield for God. One angel was recorded as having killed thousands of soldiers with one swing of his heavenly sword. Angels, you see, aren’t the androgynous, winged, lute-playing entities that we are familiar with from art. They’re God’s messengers and soldiers; warrior-diplomats. So perhaps Gabriel appeared more like Brian Blessed in his role as the Duke of Exeter in Henry V delivering the declaration of war to the French–perhaps he came in armor, bellowing his greeting, teeth flashing. What did this messenger of God mean for her? And why would she, a woman of low estate engaged to be married to a carpenter, be thought highly favored? And what must she have thought when Gabriel continued his message to her? What did he mean when he told her, “you will conceive in your womb and bear a son, and you shall call his name Jesus. He will be great and will be called the Son of the Most High. And the Lord God will give to him the throne of his father David, and he will reign over the house of Jacob forever, and of his kingdom there will be no end“? Surely, could such a thing be possible? She wasn’t even officially married to Joseph yet, though betrothal bore with it many of the legal considerations that come with marriage. How could she have a child if she had never known any man, not even her intended? What did this messenger from God mean?

When we think on what Gabriel tells Mary, I am not sure that we fully appreciate what is going on here with Gabriel’s annunciation. We know the end result, so perhaps it doesn’t seem so momentous to us, so utterly strange, wonderful, and not a little bit frightening. Here we have Mary, just a young woman going about her daily business, when God’s messenger appears out of nowhere to tell her that she is going to have a baby and that God is going to be his father. I think were we in Mary’s position, we might have said something along the lines of, “you’re kidding me!” or “are you insane–that’s not possible?!” “Giving birth to God, really?” People don’t just have babies without having enjoyed the marriage bed first. But this is what Gabriel told her. And though she did have some trouble accepting it initially, she believed him, and to do that took incredible faith on Mary’s part.

In one of Martin Luther’s writings about the Annunciation, he cites something said by St. Bernard of Clairvaux, who lived in the 10th Century. Luther says:

“…Saint Bernard declared there are here three miracles: that God and man should be joined in this Child; that a mother should remain a virgin; that Mary should have such faith as to believe that this mystery would be accomplished in her. The last is not the least of the three. The Virgin birth is a mere trifle for God; that God should become man is a greater miracle; but most amazing of all is that this maiden should credit the announcement that she, rather than some other virgin had been chosen to be the mother of God.”[1]

The incarnation and the virgin birth are easy things for God. He’s omnipotent, so taking on human flesh and becoming one of us, or being born from a virgin, is small potatoes. (Everything for God is small potatoes, really). And what God does is often illogical to our human reason. St. Augustine says in one of his Christmas sermons:

…the Virgin Mother, from the fruitfulness of her womb and with her virginity preserved, brought forth Him who was made visible for us and by whom—invisible—she herself had been created. A virgin who conceives, a virgin who gives birth; a virgin with Child, a virgin delivered of Child—a virgin ever virgin! Why do you marvel at these things, O man? When God vouchsafed to become man, it was fitting that He should be born in this way. He who was made of her, had made her what she was.[2]

Have fun wrapping your minds around that! When God became one of us, he chose to be made a baby by a woman he himself had made. That is both a miracle and a paradox. But that’s still not the greatest miracle. No, the greatest miracle is Mary’s accepting faith.

For Mary, to say “Let it be unto me as you have said” took incredible faith. Here you have a young woman who’s probably not out of her teens who has just been approached by the messenger of the Lord with the news that she would bear the Lord’s Messiah in her womb and that this child would be born to her with her keeping her virginity intact. And that God would be his father, and that this child himself would be God. She hears all this and says, “Yes, let this be so” upon hearing the angel’s explanation of how God would bring this about in her. There’s no objection, no bargaining, no further questions, no argument; she just says, “yes.” Mary had to be very secure in her trust toward God in order to say yes in this way. She had to believe that God would do what he said he would do and that she would be fine. She had to trust him above all else, because all of this was a risk.

Think about it: childbirth for a woman in the 1st Century was dangerous. Many women died while birthing their children. Jesus would be God’s Son, but would she, Mary, survive the ordeal? And then there’s the problem of being an essentially unwed mother. Sure, Joseph was essentially her husband now, but how could she explain this surprise pregnancy? And how could she tell him that God was the father? Would he even listen? Joseph could think that his betrothed was running around on him. How would he take the news? And what would all of Nazareth think? But when Mary hears that this will all be possible on account of the Holy Spirit, Mary steps out in faith and says to the angel Gabriel, “Let it be for me as you have said.”

Luther says that Mary “held fast to the word of the angel because she had become a new creature.“[3] She was made a “new creature” because of the faith that God had granted her through the Holy Spirit. She heard the promise that the Messiah would be coming soon, and coming soon through her, no less. The Messiah who would bring an end to sin and death and hell would be her child. When presented with a promise like that, with that great hope, spoken by God’s emissary speaking with the voice of God himself, how could she not be changed? How could she not believe? How could she not have faith that this would be so?

And Mary’s faith is an example for us. So often, we have difficulty trusting God’s will for us, or trusting that he is caring for us. This last year has shaken a lot of people’s faith. Between the pandemic, the shutdowns and their accompanying economic and social worries, the summer’s racial unrest and riots, the contentious election–these are all things that have caused some of us to question what God’s plans are for us, or whether God actually means well for us. And so many people have suffered all manner of personal tragedies–loss of loved ones to disease, old age, accidents, violence. Sin is everywhere, as are its effects. Where is God and his promises in the midst of all this darkness? And given the darkness that surrounds us and that we experience, directly or indirectly, every day, how can we believe that God’s promises to us for deliverance are real and true? Sometimes, it sounds outlandish, even impossible, that the promise of Christ’s return is true; that Christ indeed died for us. Luther puts it this way: “This is for us the hardest point, not so much to believe that He is the son of the Virgin and God himself, as to believe that this Son of God is ours.”[4]

But the miracle of Mary’s faith and her “yes,” as Luther says, happens to us all. “We must believe by faith what will be against our presuppositions, thoughts, experiences and examples” (Luther’s festival sermons, p.274). God’s promises to us do not fit within our experience. They don’t necessarily make sense given what we know of the world around us. But Mary is our example, because what she was told did not fit within the realm of her lived experience, either. Who gets a visit from an angel telling them that they will be giving birth to God in the flesh? But Mary “believed. She closed her eyes even if her reason and all creation were against it. Her heart clung only to His Word” (Luther’s Festival Sermons, p.275). And in clinging to his Word, Mary did receive precisely what she was told she would. She brought forth a Son and gave him the name Jesus, and he grew up to be the Savior of the whole world.

And so we should also cling to God’s promises, just like Mary, even if they seem to go against everything our senses tell us, because God makes good on his promises to everyone, and moreover, we have a distinct difference. Mary had to wait to see the promise God had given to her realized. But we know about what Jesus came and did. We know that it came to pass, and that Jesus did indeed die and rise again for us for the forgiveness of our sins and to destroy the darkness that characterizes our world and which assails us from without and from within. We can trust the word of God that Jesus has come and is coming again, and cling to it because what Jesus has done makes it true. Like Mary, we can “cling to God’s Word and close our eyes” to those things which try to distract us or harm our faith. “The Word of God is a living Word which death cannot defeat. Where that Word remains, there you also remain” (Luther’s Festival Sermons, p.275). So cling to that life giving word, made like the blessed Mother of our Lord into new creatures, alive in the promise of Christ and his coming. Amen!

[1] Martin Luther. Martin Luther’s Christmas Book (Kindle Locations 136-150). Kindle Edition.

[2] Augustine, “Sermon 4,” in St. Augustine: Sermons for Christmas and Epiphany, ed. Johannes Quasten and Joseph C. Plumpe, trans. Thomas Comerford Lawler, vol. 15, Ancient Christian Writers (New York; Mahwah, NJ: The Newman Press, 1952), 80. (Ben. no.186).

[3] Martin Luther. Martin Luther’s Christmas Book (Kindle Locations 136-150). Kindle Edition.

[4] Martin Luther. Martin Luther’s Christmas Book (Kindle Locations 136-150). Kindle Edition.